As I mentioned in my previous post, Jon and I went on a two-week holiday to Spain at the end of August. It was an amazing time and we got to hang out with my family, who live in the US, and whom we hadn’t seen since 2019. Unlike previous international holidays, such as our honeymoon in Barcelona or our later trip to Valencia where we mostly stayed in one city, this time we visited the entire central axis of the country, from the Basque Country to Andalusia. I will share the main highlights of the trip from an accessible transport perspective, showing both the good and the bad.

The Itinerary

Because of the multiple destinations and the difficulties with hiring portable hoists and shower chairs at all our locations, we made the choice to travel in our large wheelchair-accessible van and take all necessary items with us. Even with driving, our trip still made extensive use of various transport modes, including metro systems, ferries, commuter trains, high-speed rail, and buses. Our trip consisted of a 24-hour ferry from Portsmouth to Bilbao, 4 days in Bilbao (with day trip to San Sebastian), 4 days in Madrid (with day trip to Toledo), 4 days in Seville (with day trip to Cordoba), 2 days in Salamanca, and the return journey to the UK via ferry from Bilbao.

With so many destination, we had a great opportunity to assess the state of transport accessibility of some of Spain’s most prominent cities. Barcelona is frequently singled out for its amazing accessibility, both in its transport network and in its general environment, but it is far from the only Spanish city to have made significant process in becoming a welcoming place for disabled people. During our trip, we were able to successfully navigate almost all our destinations with relative ease, particularly through the centre of these major cities.

Unfortunately, the glaring exception to this was Toledo. Despite its centre being breathtakingly beautiful, its lack of suitable pavements, accessible venues, and dropped kerbs, as well as its very steep streets, made the day trip a really stressful experience. (Toledo actually flooded the day after we visited, so I suppose it could’ve been a lot worse!).

Overview of Spanish Urban Transport

The rail transport situation in Spanish cities is largely comparable to that of UK ones. In both countries, pre-WW2 rapid transit systems were built for the two largest cities at the time (Madrid and Barcelona, and London and Glasgow), and additional urban rail networks, in the form of trams, light rail, and metro systems, for smaller cities would take until the 80s and 90s to materialise. All in all, Spain has been more successful in building up segregated light and heavy rail metro systems for its major centres, with Valencia, Bilbao, Seville, Malaga, Palma de Mallorca, and Granada boasting of these networks, and smaller cities having small tram networks.

By contrast, high-capacity urban rail systems outside of London and Glasgow are limited to Merseyside and Tyne and Wear, with some of biggest cities in the country relying on trams to do the heavy lifting (Manchester, Birmingham, Sheffield) and other major cities not having introduced any urban rail transport (Leeds, Bristol) apart from buses. Had the UK followed a transport policy similar to Spain, all major cities in the UK would have multi-line metro systems, and cities the size of Oxford and bigger could credibly support tram lines.

Complementing the urban transport in both countries, the national railway network of each country includes commuter networks centred on the major cities. These vary widely in size and frequency, ranging from fully-fledged systems and multiple operators to single lines or disjointed networks with limited service. Generally, these systems are aimed towards serving the wider metropolitan areas rather than optimising coverage through the urban cores, so they are not a good substitute for dedicated rapid transit.

Degree of Accessibility

Looking at accessibility in Spain, the long time between the introduction of the legacy metro systems in Madrid and Barcelona and the modern networks elsewhere means that these newer networks were built with accessible design built-in from the start. When we were in Bilbao, which has a three-line metro system in addition to trams, regional and commuter rail lines, it was great being able to travel all around the city by metro without having to worry about inaccessible stations or needing staff assistance.

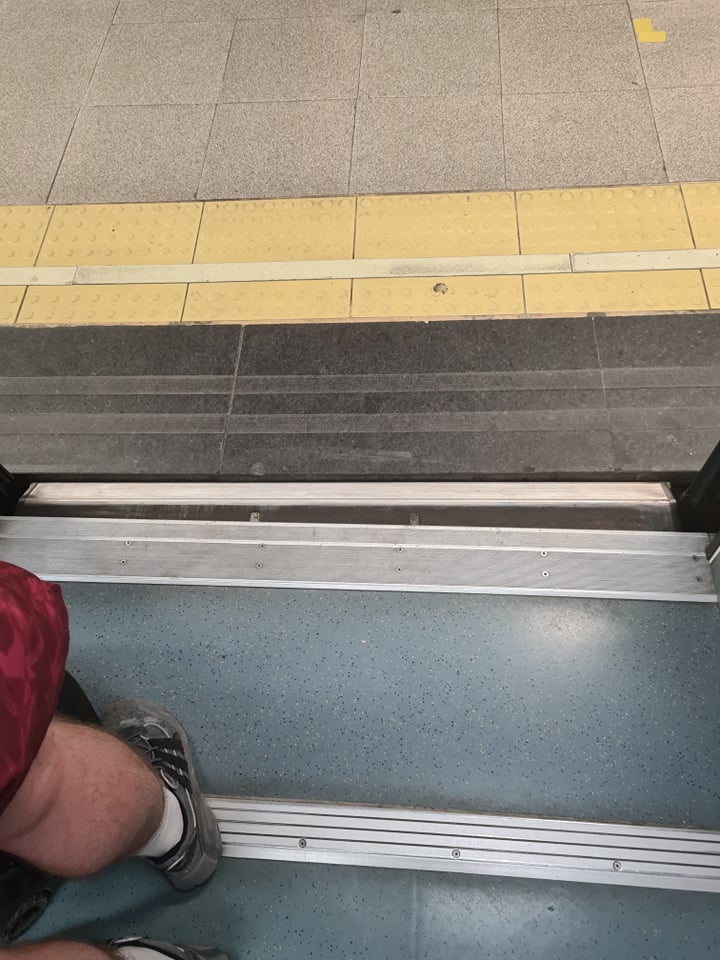

However, one thing to note is that the definition for level boarding in practice seems to be noticeably stronger in the UK relative to Spain. For example, Seville’s single line metro opened in 2007, and its platform-train interface (PTI) is less than impressive. Here is a short video at San Bernardo station.

We actually had to use a small portable ramp to board the train, which was shocking for a new system. As an aside, I highly recommend getting a small portable ramp when travelling abroad, we made good use of it both in and out of stations! In any case, this is something that needs to be rectified immediately. If Jon’s large wheelchair is unable to climb onto the train, I can only imagine how smaller chairs would fare. Also, in all the metro systems we travelled in, we found virtually no platform and very limited gateline staffing, so it is not clear what we would have done without our ramp.

Even in Bilbao, when we went to the outskirts of the city near the port, we noticed a significant variation in the step and gap at some stations, particularly the above-ground ones. This is fortunately something that is will be improved in the future, as Metro Bilbao plans to embark on a pilot programme to reduce the PTI at its most difficult stations (in Spanish). Luckily, we didn’t have any issues in Bilbao.

Madrid

Newer systems are simple when it comes to accessibility, as you tend to have a largely uniform station design and associated rolling stock. It is older systems where things get a bit weirder, and the Madrid Metro is a very interesting case study for accessibility. Compared to the London Underground and the Paris Metro, both of which are known for their poor coverage of accessible stations, the Madrid system has achieved incredible success with expanding accessibility (although not quite as much as Barcelona, which had an earlier start and smaller system). Similar to these other two cities, Madrid did not start installing any lifts until 1994, which is comparable to the first accessible line in Paris (M14 in 1998) and in London (Jubilee Line Extension in 1999).

Since then, Madrid has raced past both cities, not only with new lines, but with an incredibly ambitious accessibility programme that has reached roughly 2/3 of the network (204/302). Unlike the Underground, the Madrid Metro counts each set of platforms at interchange stations as individual stations, so it is not possible to directly compare this value with the Underground’s 89/272 step-free stations, but it is clear that Madrid has made a much more meaningful investment in accessibility.

Accessibility Investment

A sum of €141 million was budgeted for 2016-2020 for accessibility measures, which included the step-free access works for 36 stations, corresponding to 16 when grouping together platforms in the same interchange stations (in Spanish). As is unfortunately all too common the schedule has slipped, partly due to the pandemic, and 16 of the 36 stations are yet to be delivered, of which 12 are under construction and 4 are awaiting approval. Despite this, the regional government of Madrid announced a new accessibility investment this summer for 2021-2028 (in Spanish), in addition to the still-undelivered stations. This investment is composed of 332 million euros, and will make an additional 28 stations accessible (24 after grouping interchanges). This means that there is a plan to have 82% of the network be step-free, and there is a credible path to achieve complete coverage in subsequent stages.

The plans for the London Underground made during this time period are much more uncertain and rather chaotic. In December 2016, Mayor of London Sadiq Khan announced a £200m investment over the next five years to increase the percentage of step-free stations from 26% beyond 40%, which would mean at least 109 step-free stations out of 272. This headline news would have been incredible had it actually happened, and would’ve matched Madrid’s ambition, with a total of at least 39 new step-free stations, including those that were already under construction or part of the Crossrail works. Since the announcement almost 5 years ago, 19 Underground stations have gained step-free access, for a total of 89 step-free stations. However, TfL’s dire finances even before the pandemic have all but destroyed any momentum in step-free access, with many schemes now unfunded and deferred indefinitely or into the next decade. It seems even TfL was always unsure about its original ambition, as a full list of the 39+ stations was never actually released.

Even if the funding had not evaporated, TfL’s approach to step-free access has relied mainly on prioritising easy wins in Outer London and heavily depending on outside developers rather than forming a cohesive long-term strategy that tackles busy interchange stations and ensures an even spread of step-free coverage. On the other hand, the Madrid metro has an explicit priority system, where multi-line interchange stations are at the front, followed by remaining interchange stations, and finally single-line stations based on their passenger numbers and value. With its focus on interchange stations, Madrid has had to put up with significant disruptions as large numbers of major stations are simultaneously under construction, but the result is that the most challenging works are being done first to give the maximum benefit and to create momentum for the remaining works.

In London, there has been no similar prioritisation, with full step-free access at major stations like Leicester Square, Oxford Circus, Charing Cross, Piccadilly Circus, and Baker Street being completely absent in all pre-pandemic step-free access planning. Even announced schemes at Euston, Holborn, Camden Town, and South Kensington have been repeatedly pushed back with no start date in sight. To make matters worse, the pandemic’s ongoing effects on TfL’s finances mean that there are no new schemes being planned. The UK Government and London need to follow Madrid’s example and prioritise an accessibility revolution in London that isn’t bogged down by petty politics and that puts passengers first.

Level Boarding Fails

One thing that Madrid unfortunately gets very wrong is the lack of distinction between step-free to platforms and step-free to trains. When trying to ride on Line 1 of the Metro from Atocha to Sol, two major stations, we were disappointed to find that the old rolling stock of the line created a notable step between the platform and the train. We were again unable to find any staff member, as the metro gateline at Spain’s busiest station was unstaffed, but luckily in the end we were able to use our portable ramp to board.

That this information is not publicised is incredibly negligent and potentially dangerous. This also needs to be immediately rectified, and there needs to be a clear plan to ensure that accurate information is available to passengers.

Another major issue we had with level boarding in Madrid was trying to use the commuter rail system, known as the Cercanias. In Madrid, approximately 72% of Cercanias stations (65/90) are step-free, but only some of the rolling stock is equipped to offer level boarding at the standard platform height for commuter trains, which is 680 mm above the rails. In our previous trips to Spain, we found that the majority of commuter trains in Barcelona and Valencia were equipped with a low-floor carriage that allowed for level boarding.

Even on this trip, we had no problems in Seville, even though the frequencies of the network were disappointingly low.

However, after having to see 7-8 inaccessible trains go past in Madrid’s busiest section of the Cercanias network between Atocha and Nuevos Misterios (shared by 5 commuter lines and more than 12 trains per hour), I am convinced that Madrid should immediately stop pretending that its Cercanias network is anything other than an incredible disgrace regarding accessibility.

Not only is there no way to check in advance if a given train is adapted, and the inaccessible trains don’t seem to be rampable, but also the the sheer number of inaccessible trains that we saw in the core section of the network probably means that some of these lines don’t have any accessible trains! So for the Cercanias network to advertise itself as being an accessible mode of transport is incredibly deceitful.

I talk a lot about level boarding, and lack thereof, in the UK, and would love to see the widespread rollout of level boarding carriages that Spain has. However, as the rollout moves forward and there is a prolonged transition period of level boarding and inaccessible trains, it is imperative that resources are available to keep passengers informed, because this is unacceptable.

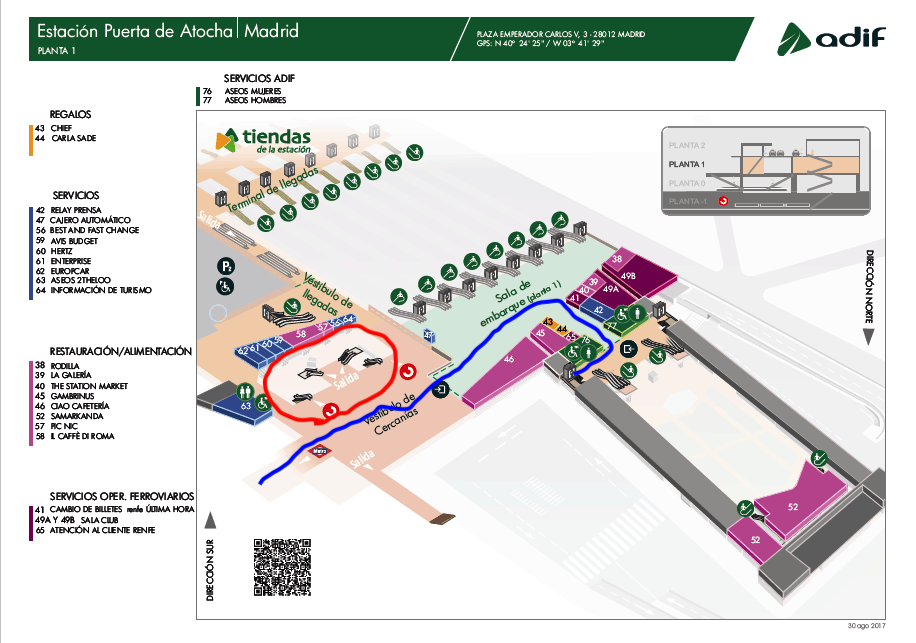

It also did not help that I found the huge Atocha station complex, which roughly corresponds to King’s Cross St Pancras in London, to be an unmitigated disaster for accessibility. Even before trying to use the Cercanias network, we found that there is no public step-free access to the Cercanias platforms if you use the lift closest to the entrance of the Metro. So we spent 30 minutes trying to find a lift that didn’t exist (allegedly it will soon exist) before a member of staff took pity on us and led us through the security area for long distance services and out the other end of the station where the only set of usable lifts were located. I thought Paris Gare du Nord was bad, but Atocha was even more torturous and time-wasting, with its airport-style atmosphere and appalling signage.

Integrated Transport Modes

Talking about inadequate resources, one thing that stood out in this trip is the chaotic relationship between different rail systems in the same city. Similar to Manchester and Birmingham and unlike London, the urban transit and commuter networks in most of Spain function completely separately from each other, with no joint fare structure or single payment method. This means that it can require multiple fares to complete journeys managed by different operators. In Bilbao, even the tram requires a different ticket than the metro.

All of this results in competing networks that don’t benefit passengers and seamless travel. You can’t even find an official railway map showing both the Madrid metro and its Cercanias network! TfL is guilty of doing this in London, but at least there is the London-wide Rail and Tube Map that accurately depicts the entire scope of rail transport in London (even if it doesn’t include accessibility information). Hopefully these cities, both in Spain and the UK, eventually adopt a joint outward approach to their public transport networks, even if there are multiple operators, and allow passengers to make full use of them.

Novel Level Boarding

Interestingly given the issues with Line 1, the Madrid Metro also had one of the most ingenious solutions for level boarding that I’ve ever seen. The trains on Lines 2-5 have the accessible doors at the front of the train near the driver, and these doors are equipped with a novel gap filler that completely bridges the gap between train and platform, even when the gap is variable across the length of the door for curved stations. This gap filler is part of the train, and appears to be deployed remotely by the driver when someone requiring step-free access is attempting to board or alight. Unfortunately, we didn’t get the chance to explore this system further and see if there is an interior button to alert the driver to operate the gap filler, but the fact that the gap filler can be angled brings new hope that this solution could be widely used for other old metro systems like the London Underground.

High Speed Railway

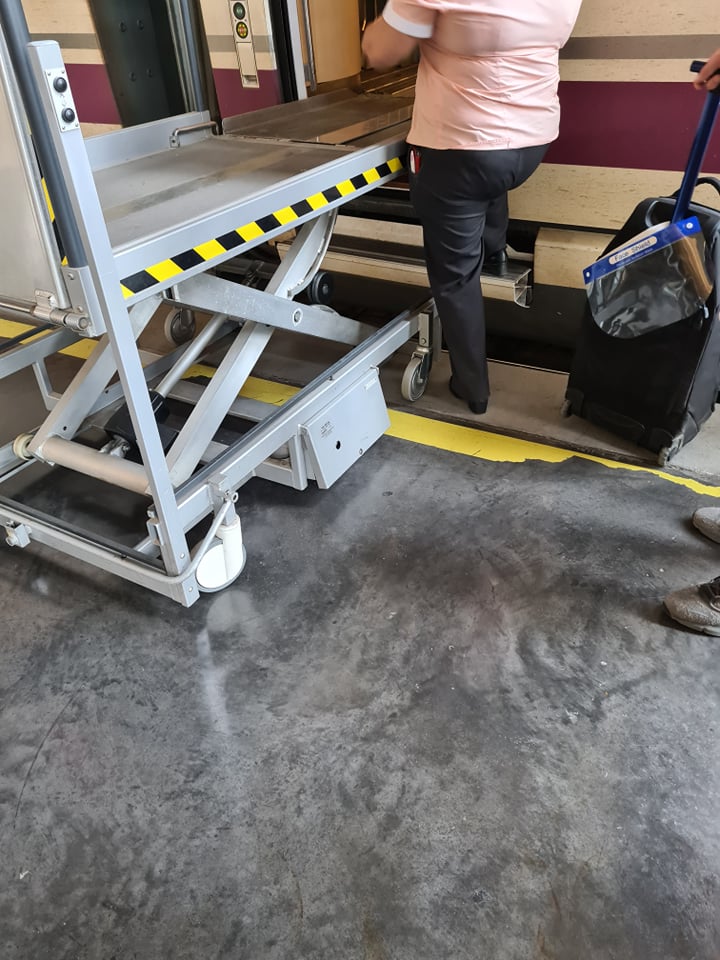

The last point I want to make on Spain is regarding the intercity rail network. On this trip, we made two round-trip journeys on the national railway network, the first from Madrid to Toledo, and the second from Seville to Cordoba. Both of these journeys were on Spain’s incredible high speed rail network, and unlike the Cercanias networks, where level boarding is slowly becoming widespread, intercity rail platforms are lower and the PTI’s are enormous, requiring huge ramp/lift contraptions to board the trains.

This means that booking ramp assistance is necessary. I am not sure how far in advance ramp assistance needs to be booked, but for us, we were able to automatically request assistance when we bought the tickets the day before on the operator’s website.

This was pretty convenient, and the assistance staff in the station were expecting us and ready to help. One thing that was a bit annoying was that you were also expected to be at the assistance office 20-30 minutes before departure. This may seem fine if you are taking a long-distance journey, but seeing as both journeys we made were under 45 minutes, it seemed a bit excessive, especially when other passengers could board almost up until departure time. While I understand that turn-up-and-go travel is much harder to offer given the more involved ramp process, this is a major inconvenience for disabled people commuting regularly.

It was interesting to see the extreme differences between travelling on the Cercanias trains and travelling on the wider railway network with regards to assistance and the boarding process. In the UK, the line between commuter and long-distance travel is extremely blurred, especially in the South East. Living in Reading, we are extremely spoiled to have a huge number of slow and express services into London, all valid with the same anytime ticket and with turn-up-and-go ramp assistance for all services.

Level Boarding High Speed Train?

There are hints that the new high speed Talgo Avril trains, much like the upcoming trains for the French high speed network, will finally bring the first instance of level boarding on the mainline railways. I have still yet to see definitive video evidence of a wheelchair user independently boarding one of these trains, so we will need to wait and see if these claims are true. Hopefully within a few months, accessibility will receive a much needed boost for intercity travel.

Quick UK Highlights

Back in the UK, since it took me so long to get this post out, I will just mention some of the most important developments of the past few months.

New Step-Free Access

Most importantly, we have new step-free stations in London! With the opening of the Northern Line Extension, there are now two new step-free stations with level boarding at Nine Elms and Battersea Power Station. Unfortunately, despite being brand new stations in a completely redeveloped area of London, there are some very disappointing design issues that affect the quality of accessibility, such as small lifts, lack of resilience in lift provision, and a bizarrely complicated lift system at Battersea park, among other issues. This brilliant Twitter thread by Alan Benson does a great job at highlighting all these problems.

And as was widely expected, this is the inevitable result:

Looking at existing stations, Hayes & Harlington’s completed lifts mean that all the stations from Paddington to Reading are now step-free to platform. And after 3 months of unexplained delays, Osterley is the latest Underground station to be made step-free. This means that it will be either Sudbury Hill or Harrow-on-the-Hill that will take the Underground past 33% step-free access. Not quite the 40% we were promised, but progress is progress.

Tragedy of Unsafe PTI

Showing the devastating results of the London Underground’s world famous gaps, the Rail Accident Investigation Branch last month released its report on a fatal accident at Waterloo’s northbound Bakerloo Line platform. The harrowing incident, caused in no small part due to the curved platform’s monstrous gap, is a sobering reminder that accessibility and level boarding, and lack thereof, are key safety matters that have real-life consequences for all passengers. The rail industry needs to take this horrible accident seriously and put together a concrete plan to improve the PTI across London and the country, as this type of dangerous platforms is unfortunately not especially rare. “Mind the Gap” may be synonymous with the London Underground, but it really shouldn’t, and there are plenty of innovative solution around the world, such as in Madrid, that could begin to remedy the situation.

More Pictures!

To finish up on a lighter note, here are some extra pictures from the Spain trip!

Jon and me in La Plaza De España of Seville

Jon and me in La Plaza Mayor of Salamanca

Jon in the Mosque–Cathedral of Cordoba

Jon and me in the Alcazar of Seville

Jon, my friend Calvin, and me outside the Royal Palace of Madrid

Jon an me in El Retiro park in Madrid

Jon and me in a wine cellar at Bodegas Ismael Arroyo-ValSotillo winery in Sotillo de la Ribera

Jon and me in La Plaza Nueva in Bilbao

Jon and me in the harbour of San Sebastian

Jon and Me on the ferry leaving Portsmouth

Jon, my family, and me in Moyua in Bibao

Typo spotted – Had Spain followed a transport policy similar to Spain, all major cities in the UK would have a multi-line metro system,

Thanks! Its fixed now

TFL has begun a consultation on tge future of step free access with questions like whether funds be spent on one large scheme or several smaller schemes etc. It also mentions work for 3 paused schemes is getting underway Burnt Oak, Hanger Lane and Northolt .

See – https://tfl.gov.uk/info-for/media/press-releases/2021/november/tfl-asks-customers-to-help-shape-the-future-of-step-free-access

I have filled in the survey. Thank you for the info! Although I may not be of much help since I’m from overseas, I still am of the opinion that they should use the plug-gap method, as well as prioritising stations with high elevations or deep underground cuz that’s where commuters most need em. I’m surprised they didn’t mention a priority is to make stations near grocery hotspots step-free.

Crowborough and East Grinstead Stations to benefit from Access for Funding –

https://www.networkrailmediacentre.co.uk/news/crowborough-and-east-grinstead-stations-both-benefit-from-step-free-access-for-the-first-time-thanks-to-over-gbp-9m-invested-to-improve-accessibility

Seems property development linked to South Kensington Station upgrades with step free access was blocked last night . See –

https://www.ianvisits.co.uk/blog/2021/11/19/south-kensington-tube-station-property-redevelopment-blocked/

However, Kensington and Chelsea Council are looking at ways to fund step free access if development doesn’t .

Canterbury East Station gets its lifts under Access for All scheme-

https://www.networkrailmediacentre.co.uk/news/access-for-all-at-canterbury-east

Spotted on Twitter re Waterloo and City Line –

Transport for London

@TfL

·

7h

Waterloo & City line has resumed a full weekday service from 6am until 12:30am

Use our travel tools to plan your journey around the network and check for disruptions

SWR South Western Railway has introduced assistance boarding points at stations see link below-

https://www.railtechnologymagazine.com/articles/south-western-railway-assisted-boarding-points

Sudbury Hill becomes underground 90th step free station see press release below-

https://tfl.gov.uk/info-for/media/press-releases/2021/december/sudbury-hill-becomes-london-s-90th-step-free-tube-station

Ending a successful year for access improvements for TFL let’s hope the departure of Deputy Mayor Heidi Alexander won’t affect future plans

The DFT have published a new contract with C2C railway and I spotted the following plan for Dagenham East Station-

Reinstate Dagenham East station between Upminster & West Horndon to support LondonEast – Business and Technology Park

Dagenham East is not currently accessible so if this plan goes ahead it will probably provide a new fully accessible interchange between the District Line and C2C.

Lifts are also mentioned for West Herndon Station without any guarantee.

Minor typo – It was Sudbury Hill that just went step free and needs to be removed from future stations list .

I noticed new tube map on TFL site fails to show W&C stations as step free !

Thanks!! And yes shameful!

Plans for an additional Elizabeth Station ( Twyford Gardens) in Berkshire although only at an early stage and linked to development proposals –

https://www.ianvisits.co.uk/articles/plans-for-an-additional-elizabeth-line-station-in-berkshire-50706/#comment-259026

Seems quite uncertain at this moment!

News of work at Euston Station linked to HS2 including links to underground are progressing. See link below-

https://www.constructionenquirer.com/2022/02/14/tier-2s-set-for-500m-of-hs2-euston-station-work/

It seems former District Line trains are to be used for battery trials on the Greenford branch . So whether these trains will improve accessibility at the stations that are not fully staffed will have to be seen . See –

https://www.ianvisits.co.uk/articles/ex-london-underground-trains-to-be-tested-on-the-greenford-branch-line-51960/

Im doubtful about any improvements in acessibility, seeing the mess that was made in the Isle of Wight. Only this time there is less incentive to use non-standard platform heights.

Level boarding test on central Crossrail station –

https://twitter.com/KatiePennick/status/1495109058969452547?s=20&t=yTeNDydQmQsmZUeTc60iZw

East Grinstead Station to become step free autumn 2022 Network Rail details –

https://www.networkrail.co.uk/running-the-railway/our-routes/sussex/sussex-railway-upgrade-plan/step-free-access-for-east-grinstead-station/